- Home

-

Poetry

- Community development

�

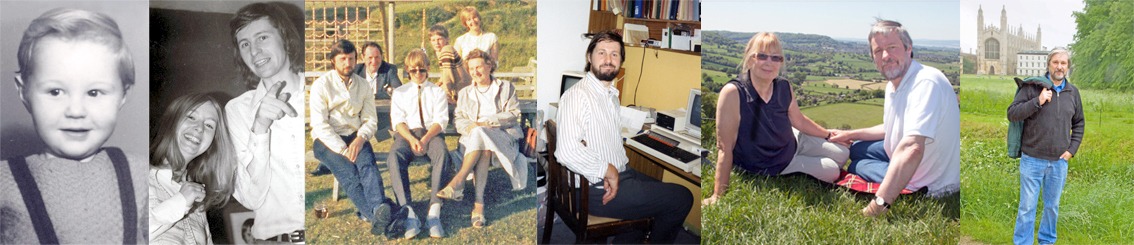

THIS IS ME

I was born in 1948, six months before the NHS, which I have resembled by being largely well-intentioned, persistently less efficient than I ought to be, and somewhat accident prone.

My Dad Jack was a workaholic electrical engineer who pioneered automation at the board-making company where he worked for almost his entire career. My caring and hyper-energetic Mum Doris, who was more talented than most of us recognised, worked as a part-time book keeper but spent nearly half her life looking after my grandparents who lived with us. She didn’t get round to providing me with a sister till I was nearly 10, which made me an odd kind of only child who also had a sibling to care for and spar with.

My childhood in the London dormitory town of Maidenhead passed entirely happily, apart from the occasional cruelties of scouting and school swimming lessons. My freedom to roam the country on my bike and by train was unlimited. I had great friends, and also had no problem entertaining myself on my own. It seems a privileged lifestyle compared with those of youngsters today.

Adults also seemed oddly keen to point out that I was receiving a “privileged” education – as if I was supposed to know my place. This was at the single-sex Maidenhead Grammar School, where I spent an exuberant and precocious time as the editor of newspapers pinned to classroom walls and occasional duplicated magazines.

Me and my camera: It’s said that since the advent of digital photography it’s impossible to get a picture of me without a camera in my hand

Me and my camera: It’s said that since the advent of digital photography it’s impossible to get a picture of me without a camera in my handI took a glorious gap half-year delivering telegrams on a post office motor-bike before starting on a genuinely privileged education reading English at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge – where the predominantly public school educated students taught me what real privilege was like. It was their vast self-confidence rather than affluence which was so overwhelming.

I hid away for three years with a small group of friends, emerging occasionally to run a college poetry group, to contest a junior common room election as the nihilist candidate (disappointingly three people failed to get the joke and voted for me), and directing a self-written play The Goldfish in college immediately after our finals.

Looking back on the 1970s, the lack of political stability in the country seems to have been mirrored in the way I was leading my life. The antidotes to the three glorious years in the museum-like splendour of Cambridge were seven months on the track at Vauxhalls in Luton fixing brake pipes to Bedford vans, then a failed attempt to write a novel and a doomed attempt to be married. After a year I went hunting for a job in journalism and discovered I was now too old for a traineeship and too expensive for any responsible unionised paper to employ. Which is why my only job offer was from a tiny maverick weekly serving the Valleys of South East Wales where I learned to write and edit copy, lay out pages and live on £1,000 a year.

After spells on the more respectable South Wales Argus and Western Mail, where I became Labour Correspondent, I was seized one dull slow-news afternoon by a crazy idea. Why not turn the free monthly community newssheet Cwmbran Checkpoint, which had been set up by the local charity Community Projects Centre, and which I was then editing, into a volunteer-run weekly newspaper funded by sales and advertising? I was by now father to the irrepressibly cheerful baby David, and even so another irresponsible new idea emerged almost simultaneously: to not be married. Sue has been a great support in pursuing this alternative status over the past 40 years or so, and I’ve had a most rewarding paternal part-share in her two boys, Geraint and New Zealand emigré Rhodri.

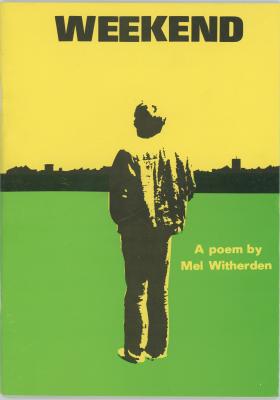

“Weekend”: I always intended to print Weekend, my first book of poetry, using printing equipment at Cwmbran Community Press. But I never got further than making the plates for it. When I left CCP the staff presented me with the completed book which they’d printed in secret. It’s probably the best present I’ve ever had.

“Weekend”: I always intended to print Weekend, my first book of poetry, using printing equipment at Cwmbran Community Press. But I never got further than making the plates for it. When I left CCP the staff presented me with the completed book which they’d printed in secret. It’s probably the best present I’ve ever had.Amazingly there was also a tremendous team of Checkpoint volunteers who were prepared to support the bizarre venture into weekly journalism, and we registered Cwmbran Community Press (CCP) as a limited company in 1976. Later we became printers and local history publishers, we ran training projects, and over the course of a dozen years we attracted hundreds of volunteers, establishing an entirely new way to run a financially self-supporting business. More long lasting have been the marvelous friendships which started in the Checkpoint days, and memories of a deleriously happy social life lubricated inexpensively with home-made beer and wine.

It was also during this period that I helped to set up a branch of the Green Party in Cwmbran after the surprise discovery of a party manifesto which actually chimed with my own vision for society and with my disdain for conventional politics. I fought three UK parliamentary elections for the Greens, with results which were even poorer than my modest expectations. But at the 1989 European Elections we did spectacularly well in the Labour’s South East Wales stronghold, almost beating the second-placed Tories.

My subsequent involvement in a pioneering Green-Plaid Cymru-Communist coalition aimed at uniting the environmental left stoked up anti-Welsh bigotry among vocal Greens in North Wales. They effectively drummed me out of the party. Green politics was after all like that of any other colour, more about fighting one’s colleagues than fighting the cause which united us. And that wasn’t for me. Apart from acting as press officer in an anti-Iraq War campaign I’ve left political activity behind me, and reverted to total despair with the entire system.

By the end of the Eighties I was getting itchy feet at CCP. We were winning the case for proper government support for projects like ours, and I wanted to share the remarkable success of CCP and our unique ways of working with other community groups. I took a job briefly helping to set up community-run businesses in Aberdeen. When this didn’t work out I came back to Wales and shortly afterwards the Welsh Development Agency (the body responsible for supporting conventional business development) announced it was setting up a dedicated unit to fund and advise new community enterprise projects in the South Wales Valleys.

Using generous WDA resources, I also built up Community Enterprise Wales, a democratic network of local groups and support agencies. CEW came close to securing government money to take over the WDA’s grant making and support role, but other agencies felt they had more right to the cash, and the initiative collapsed into self-destructive infighting. The WDA wound up my unit in 1994, leaving the support role to local councils.

This was the impetus for another career gamble: working again for Community Projects Centre, but now as a “community development consultant” with any community group, charity or public agency who had the money to pay me. Consultants have to be flexible and I quickly became a business planner, project officer, researcher, advisor, trainer and mentor – basically anyone they wanted me to be. Much of the work involved helping local groups of volunteers to set up and run projects with a trading component, inching their way painfully towards the liberating financial independence which we had achieved at CCP.

Consultancy can be a precarious existence, but despite a few worrying periods I never actually ran out of work. In 2009 I left the security of Community Projects Centre to work for another seven years as an independent consultant.

My Dad died in 1998 and is celebrated in my poem What Makes Life Last. My Mum, long an advocate of assisted dying, was 95 when she died in 2015, protesting to the end that she really didn’t want to live that long.

As so many retired people say, since giving up paid work in 2015 I’m as busy as ever. I took up bridge for fun, and play badly and much less seriously than some opponents think the game deserves. For the past dozen years I have been a director of the extraordinarily impressive community development charity Action in Caerau and Ely (ACE) in Cardiff, creating work for myself variously as chair, treasurer and supervisor to senior staff. I’m still trying to write poetry. This normally happens in intermittent bursts of enthusiasm. But the last few years have happily been the most prolific since my days as a precocious student.

Rather to my surprise I’ve found that one of life’s greatest pleasures is spending time with members of the family, including our three widely dispersed sons David in Hampshire, Geraint in Swansea, and Rhodri in New Zealand, and the mainly adult grandchildrens Jack, and Alex (who entertain me online most weekends. with their blistering skill in games of crib), Cai, Macsen, Gwen and Molly.

Not a bad place to get to. And like the NHS, after 70 years, no one with the possible exception of Sue has managed to completely privatise me.

February 2025

Helen, Sue and me with college mates

and oldest friends Pete and Nick.My biggest gamble

How CCP won financial independence

Although our weekly newspaper was phenomenally hard work, it was popular and financially quite successful – until late in 1979 when our printer in Cardiff increased his prices.

Potentially we could boost income by selling sell more advertising. But that would add more pages and make printing even more costly. On top of that, our advertisers were notoriously slow payers. Although we felt quite wealthy when we totted up all the unpaid invoices, we knew that selling more ads would quickly lead to a cash flow crisis which would mean the end of Checkpoint. On the other hand, reverting to monthly publication risked losing opportunities for volunteering which was the backbone of our whole operation.

The solution was radical and extremely high-risk. The volunteer board backed a make-or-break plan to revert to monthly publication of Checkpoint, to wait for the money we were owed to come in and then to invest every penny of it in buying our own full-size offset litho printing machine and other essential printing equipment. It would save us a fortune on Checkpoint print bills. I would shift from unemployment benefit to a paid job as printer with the primary goal of generating income from outside customers in the hope that we would be able to cover all our overheads. My wage was fixed at the level of the dole plus £5.

So I became a printer in an afternoon. We bought a second hand machine, and transported it in parts to its new first floor home in our building. A friendly engineer put it back together and when he’d finished he gave me a one-hour crash course on how to run it – the only lesson in printing I ever had. An hour after that I was fighting to roll out the next edition of Checkpoint. It was a mess – though luckily the only part of the paper which was completely unreadable was the panel which apologised to readers for a possible deterioration in print quality!

It wasn’t all hard work. In 1984 when Cwmbran Development Corporation announced they would be selling off our shopping centre to the private sector Checkpoint volunteers dressed up as town centre landmarks and entered a “Sale of the Century” float in Cwmbran Carnival. We won first prize. (I was the multi-storey car park.)

It wasn’t all hard work. In 1984 when Cwmbran Development Corporation announced they would be selling off our shopping centre to the private sector Checkpoint volunteers dressed up as town centre landmarks and entered a “Sale of the Century” float in Cwmbran Carnival. We won first prize. (I was the multi-storey car park.)For the next two years we flogged away at building up a customer base producing posters, leaflets, business cards, and booklets for local community groups, businesses and private individuals. Politicians from the party which banned their staff from taking Checkpoint into council premises pragmatically came to us for inexpensive printing.

For many months the enterprise was in the balance – I would watch the sheets running through the machine and calculate penny by penny how much we would be contributing to our coffers. I worked through the night more than once to get orders out, and operated with total disregard for health and safety. Our first paper guillotine was a massive deadly ancient relic, and my cigarette ends often set light to the cancer-inducing fluids we used to clean the printing rollers. (I no longer advocate these practices.)

But printing also proved to be a great liberating force. We started planning our own local history book publishing project – launched in 1982 as Village Publishing. We could help other community groups cut their publicity costs and young volunteers came in, and commandeered the print machinery to produce their own exotic magazines. Our business activities greatly helped increase the number of volunteer jobs in the building, and we became recognised as a valuable source of informal training for people while unemployment levels remained stubbornly high.

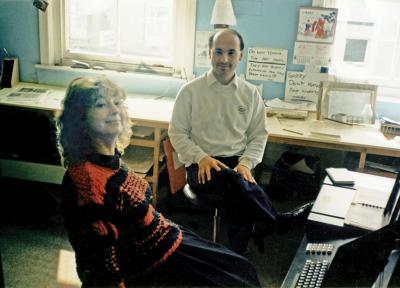

Me with visionary development worker Joe Miller in 1980. He founded Checkpoint in 1974 and asked me to join the paper’s first volunteer group. I never really left.

Me with visionary development worker Joe Miller in 1980. He founded Checkpoint in 1974 and asked me to join the paper’s first volunteer group. I never really left.Then one day I woke up to a wonderful thought: we’d been struggling for years to help Cwmbran Community Press survive, and now, even if we never received another a pound of grant money we could be sure we’d still be around the following year and probably the year after that. The sense of relief and freedom that this security gave us is hardly describable. I just wish the massive efforts of other community enterprise projects around the country could get more of them to the same delicious point. It happens far too seldom.

It was never easy, but we kept on growing. When we managed to secure a large print order we would sometimes invest the entire profit in new equipment to improve future efficiency – a second printing machine, a safe electric guillotine, professional dark room facilities, folding and collating devices and eventually our prized phototypesetting machines. Computer and IT technology has since rendered almost everything we did redundant, but for a while we were running a fairly sophisticated operation.

Typesetter Sue Reeves and Village Publishing editor Jon Preece and in 1988. We’re still friends 30 years later.

Typesetter Sue Reeves and Village Publishing editor Jon Preece and in 1988. We’re still friends 30 years later.Long hours and low wages (I can see now they were too low to maintain the levels of skill we needed) meant that we could afford to branch out into new training projects, and support for other community work in the area. When the Women’s Aid group who were tenants in the ground floor shop announced they were moving out the volunteers decided instantly to use the space for a second-hand bookshop using book donations from the public. It never made us rich, but sales income always covered the cost of the rent.

My biggest failure was in devoting too little thought to the future management of CCP before I eventually left the building in 1989. I had created a many-headed giant and used crisis management techniques to keep it alive for more than a dozen years. The volunteer board had always backed me, but I’d been unrealistic to expect anyone else could take over such a complex operation on the wages we were paying.

From my new job in Scotland I pleaded in vain for support agencies to step in to help what was becoming an increasingly rocky organisation. Then back in Wales in 1990 I joined the CCP board hoping to mount a last ditch rescue. But it was too late. The business which had been in profit when I left was bankrupt a year later with debts of over £30,000. Bad investment decisions, poor quality control and lack of financial oversight had done the damage. Naturally at the creditors’ meeting I received the blame.

It was a bitterly disappointing end. But we’d created a little piece of history. And we’d contributed to the skills, confidence and wellbeing of hundreds of people – from lonely widows and carers desperate for few hours of respite, to people who went on to successful careers as journalists, publishers, community development workers, printers etc. We’d had fun doing it, and for me it’s still the most memorable period of my life.

- Community development